"What most impressed English visitors was the Indians' burning of extensive sections of the forest once or twice a year,” William Cronon wrote in Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (1983). He quotes several primary sources of the 1600's, to explain as to why the Southern New England forest was so "park-like" and "open." In 1605, James Rosier, author of the “Voyages of George Waymouth,” felt that “It did all resemble a Stately Parke.” William Wood in 1643 put it this way: "In those places where the Indians inhabit there is scarce a bush or bramble or any cumbersome underwood to be seen in the more champion ground.”

"In short," Cronon goes on to say, "the Indians who hunted game were not just taking the 'unplanted bounties of nature;' in an important sense, they were harvesting a foodstuff which they had consciously been instrumental in creating. Few English observers saw this. To the colonists only the (Native American) women appeared to do legitimate work (in the agricultural field and gathering of wild foods); men idled away their time hunting, fishing, and wantonly burning the woods." Roger Williams may have seen this when he wrote: "(The Indians) hunted the Country over, and for the expedition of their hunting voyages, they burnt over the underwoods, once or twice a year." He was trying to defend Native sovereignty, suggesting that the Royal Grant of New England to the Plymouth Colony was illegal. In reply John Cotton, who considered native people savages and minions of the devil, wrote in reply that "We did not conceive that it is just title to so vast a Continent, to make no other improvement of millions of acres in it, but onely to burn it up for pastime."

Just this morning I came across four interesting articles.

The first is "Restoring the Cultural Landscape" by Germaine White, of the The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation in Pablo, Montana.

She writes:

"But North America was not a virgin wilderness before European settlers arrived. It was an inhabited and known land. Native peoples were not passive residents of the land. They were responsible managers who affected their environment in profound ways, and their primary and most powerful tool was fire. They burned to increase many plant food and medicines. They burned to increase game animals, because fire improved forage.

They used fire to hunt with, building drivelines and game surrounds. They kept the trails groomed with fire. They employed fire in warfare, both offensively and defensively. They cooked and warmed themselves with fire. For thousands of years Indian people more than doubled the frequency of natural fires, so much so that the plant and animal communities we have inherited today are in large measure the legacy of Indian burning.

And that is one of the pieces missing from the national conversation about fire. It is as if Indian people’s presence on the land for thousands of years has been invisible. What we need to be talking about now is the restoration of a cultural landscape."

The next is an "Essay on Native American Environmental Issues"

by David R. Lewis, taken from

Native America in the Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia, edited by Mary B. Davis and published in 1994.

He writes:

"Traditionally Native Americans have had an immediate and reciprocal relationship with their natural environments. At contact, they lived in relatively small groups close to the earth. They defined themselves by the land and sacred places, and recognized a unity in their physical and spiritual universe. Their cosmologies connected them with all animate and inanimate beings. Indians moved in a sentient world, managing its bounty and diversity carefully lest they upset the spirit "bosses," who balanced and endowed that world. They acknowledged the power of Mother Earth and the mutual obligation between hunter and hunted as coequals. Indians celebrated the earth's annual rebirth and offered thanks for her first fruits. They ritually addressed and prepared the animals they killed, the agricultural fields they tended, and the vegetal and mineral materials they processed. They used song and ritual speech to modify their world, while physically transforming that landscape with fire and water, brawn and brain. They did not passively adapt, but responded in diverse ways to adjust environments to meet their cultural as well as material desires. The pace of change in Indian environments increased dramatically with Euroamerican contact. Old World pathogens and epidemic diseases, domesticated plants and livestock, the disappearance of native flora and fauna, and changing resource use patterns altered the physical and cultural landscape of the New World..."

Of O'odham, Crow, and Chicano descent Dennis Martinez, an ecosystem restorationist, contract seed collector, and vegetation surveyor, as well as the founder of the Indigenous Peoples' Restoration Network, writes, "The latest Indian burning in Northern California and Southern Oregon was in the 1940’s. When Henry Lewis did his 1973 study of the patterns of Indian burning in California, there were people living who remembered why they burned. Now their children, who are in their 60’s and 70’s, remember burning, but they don’t remember the control techniques or the objectives. So we may have lost that knowledge.

At Three Fires Walpole Island Reserve (Ojibway, Potawattomi, Ottawa), they never stopped burning. Ontario’s 70 endangered species are found in quantity in 2,200 hectares on Walpole Island. This is amazing to botanists, who come there from all over the world to see what a “pristine” landscape can be like. But the people are part of that “pristine” quality. They’re still performing their role in the ecosystem, so the biodiversity is incredibly high.It’s the only place in Ontario where you can find biodiversity that high..."

Dr. Gerald W. Williams appears to have been a Historical Analyst for the USDA Forest Service, at least in July 15, 2003, when he wrote an introduction for something (I'll figure it out) in which he wrote:

"Henry T. Lewis, who has authored more books and articles on this subject than anyone else, concluded that there were at least 70 different reasons for the Indians firing the vegetation (Lewis 1973). Other writers have listed fewer number of reasons, using different categories (Kay 1994; Russell 1983). In summary, there are eleven major reasons for American Indian ecosystem burning, which are derived from well over 300 studies:

Hunting - The burning of large areas was useful to divert big game (deer, elk, bison) into small unburned areas for easier hunting and provide open prairies/meadows (rather than brush and tall trees) where animals (including ducks and geese) like to dine on fresh, new grass sprouts. Fire was also used to drive game into impoundments, narrow chutes, into rivers or lakes, or over cliffs where the animals could be killed easily. Some tribes used a surround fire to drive rabbits into small areas. The Seminoles even practiced hunting alligators with fire. Torches were used to spot deer and attract or see fish at night. Smoke used to drive/dislodge raccoons and bears from hiding.

Crop management - Burning was used to harvest crops, especially tarweed, yucca, greens, and grass seed collection. In addition, fire was used to prevent abandoned fields from growing over and to clear areas for planting corn and tobacco. Clearing ground of grass and brush to facilitate the gathering of acorns. Fire used to roast mescal and obtain salt from grasses.

Improve growth and yields - Fire was often used to improve grass for big game grazing (deer, elk, antelope, bison), horse pasturage, camas reproduction, seed plants, berry plants (especially raspberries, strawberries, and huckleberries), and tobacco. Fire was also used to promote or improve plants (such as willow, beargrass, deergrass, and hazelnut), as many were used for important storage/carrying baskets, clothing, and shelter.

Fireproof areas - Some indications that fire was used to protect certain medicine plants by clearing an area around the plants, as well as to fireproof areas, especially around settlements, from destructive wildfires. Fire was also used to keep prairies open from encroaching shrubs and trees. Insect collection - Some tribes used a "fire surround" to collect & roast crickets, grasshoppers, pandora moths in pine forests, and collect honey from bees.

Pest management - Burning was sometimes used to reduce insects (black flies, ticks, fleas & mosquitos) and rodents, as well as kill mistletoe that invaded mesquite and oak trees and kill the tree moss favored by deer (thus forcing them to the valleys where hunting was easier). Some tribes also used fire to kill poisonous snakes.

Warfare & signaling - Use of fire to deprive the enemy of hiding places in tall grasses and underbrush in the woods for defense, as well as using fire for offensive reasons or to escape from their enemies. Smoke signals used to alert tribes about possible enemies or in gathering forces to combat enemies. Large fires also set to signal a gathering of tribes. During the Lewis & Clark expedition, a tree was set on fire by Indians in order to “bring fair weather” for their journey. At least one tribe in the Northwest used fires set at the mouth of rivers to “call” the salmon to return from the ocean. There is one report of fire being used to bring rain (overcome drought).

Economic extortion - Some tribes also used fire for a "scorched-earth" policy to deprive settlers and fur traders from easy access to big game and thus benefitting from being "middlemen" in supplying pemmican and jerky.

Clearing areas for travel - Fires were sometimes started to clear trails for travel through areas, especially along ridges, that were overgrown with grass or brush/chaparral. Burned areas helped with providing better visibility through forests and brush lands for hunting, safety from predators (wolves, bears, and cougars) and enemies. Felling trees - Fire was reportedly used to fell trees by boring two intersecting holes into the trunk, then drop burning charcoal in one hole, allowing the smoke to exit from the other. This method was also used by early settlers. Another way to kill trees was to surround the base with fire, allowing the bark and/or the trunk to burn causing the tree to die (much like girdling) and eventually topple over. Fire also used to kill trees so that the wood could later be used for dry kindling (willows) and firewood (aspen).

Clearing riparian areas - Fire was commonly used to clear brush from riparian areas and marshes for new grasses, plant growth, and tree sprouts (to benefit beaver, muskrats, moose, and waterfowl). Species affected included cottonwoods, willows, tules/bulrushes, cattails, mesquite, as well as various sedges and grasses."

Drawing from personal experience, the author once actually worked for four days on another site that has also been continually maintained by burning since prehistoric times. Known collectively as the Blueberry Barrens of Washington County, Maine, these huge fields of “wild” native low bush blueberries (as opposed to the “cultivated” high bush type) have always been burned over on a staggered schedule every four years to keep them at peak production. Dirt road firebreaks, enabling the maintainers to selectively control which is burned and which is not, surround individual fields. The foreman, Mr. Williams, claimed it was the same manner in which Native Americans had eliminated weeds as well as fertilized the blueberries since before colonization (Personal communication August 1975).

The myth of an empty but bountiful, beautiful, and biodiverse continent, ready for settlement may fade away eventually. More will be written about the Native American’s past -and present- management of the landscape as time goes by. The original inhabitants may one day receive credit for their understanding of how to live in harmony with nature to such a degree of perfection that early Europeans mistook it for pristine, untouched Nature. Which may truly be the higher civilization: the one that scars the planet or the one that blends into and enhances the environment? Perhaps ideas will be formulated for the future, using some of this ancient wisdom.

And if you are wondering what has this to do with stones, you'll just have to wait awhile for future installments that I hope will illustrate some of the functions of some very fireproof (and waterproof) stones may have once had...

Links:

The swamp that became Lost Lake must've been dammed when I was a baby, maybe - this recent map above shows it as a body of water.

The swamp that became Lost Lake must've been dammed when I was a baby, maybe - this recent map above shows it as a body of water. This is not the actual row below, but there are many up there that look just like this pattern.

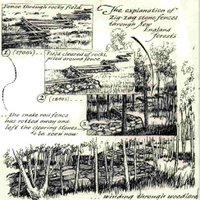

This is not the actual row below, but there are many up there that look just like this pattern. Eric Sloane in Our Disappearing Landscape offered this explaination, echoed by many other writers:

Eric Sloane in Our Disappearing Landscape offered this explaination, echoed by many other writers:

In another place, at a right angle and to the west of a very long zigzag row, an immense linear wall meets up with another zigzag row, blocked sort of by the big fallen tree:

In another place, at a right angle and to the west of a very long zigzag row, an immense linear wall meets up with another zigzag row, blocked sort of by the big fallen tree: