Tuesday, August 25, 2020

Thursday, July 23, 2020

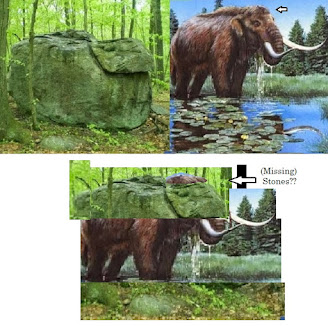

There is nothing more obvious on Turtle Island...

Sunday, November 04, 2012

Where Rye Hill Was

So of course I start wondering "Where is Rye Hill?"

And then the author let's me know in the first paragraph:

Turns out these Scrub Oak Shrublands are “fire dependant,” are found on ridge tops like they say, but also in and around “frost pockets,” ice in glacial Kettle Holes that are all over the place in that part of town, scrubbed more deeply by glacial action than anywhere else in CT except the CT River Valley. Pollen studies show evidence of intentional burning by native Americans, going way back and this pdf tells you a whole bunch about it:

And it turns out the word “chaparral” comes from the Spanish "chapa" or scrub oak...

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

1934

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Mom's Back Yard, Westbrook CT

1.jpg)

I can’t find what I started writing about last, but it was after July 5, 2008, the day I discovered the bull’s eye ring associated with Lyme Disease. It was a rough 3 weeks and then some, feeling the effects of the disease and suffering from the side effects of the anti-biotic.

But I ended up camping in my mom’s back yard down in Westbrook CT at the end of those three weeks, slowly feeling better. It's the house circled in red on this 1940's map - and found an interesting Rock Pile on a Stone Row that is the big red dot:

“Westbrook was settled in 1648 as Pochoug, an Indian word meaning "at the confluence of two rivers", the Pochoug and the Menunketesuck, by the residents of the Saybrook Colony. Pochoug was the dwelling place of Obed and his tribe until 1676. The community was incorporated as Third or West Parish in 1724 by an Act of the General Assembly.

Westbrook is the birthplace of David Bushnell, the American patriot and inventor of the submarine (He called it the Turtle). It was visited by George Washington in 1776 and by the Marquis de Lafayette in 1824.

Pochoug was renamed Westbrook in 1810 as a town by Act of the Connecticut General Assembly of 1840.”

http://www.westbrookct.us/townhistory.php?PHPSESSID=95d44b578f52c50aa0e54ee771257020

That name, Obed, pops up alot in the area:

TOWN OF WESTBROOK.By James A. PRATT

The History of Middlesex County 1635-1885J. H. Beers & Co., 36 Vesey Street, New York1884

"…(T)he Indian name of the settlement was Pochoug, a word signifying the place where a river divides, and descriptive of the location of the principal tribe at OBED's Hammock, at the confluence of Pochoug and Menunketesuc Rivers. The large quantities of arrow heads, broken pottery, shells, and other Indian remains that have been found and are being unearthed in that vicinity, are evidence that it was some time the abode of a numerous and powerful tribe.

A very common name for the western part of the town, in ancient annals, is Menunketeset, or Menunketesuc, in Indian dialect, Ma-na-qua-te-sett. The name is of Mohegan origin, and was applied to the West River, and the section bordering upon it, after its possession was claimed by UNCAS. In his deed to Saybrook, in 1666, it is written, Menunketeset, and it has been spelled and pronounced every conceivable way since. The significance of the word is lost. The soil on both sides of the rivers is a mass of shells, the remains of clam and oyster feasts before the discovery of America. A remarkable feature of the vicinity is the great number of broken or unfinished arrow heads to be found at Round Hill, on the east side of the river. The only explanation for this is, that it was the headquarters for the manufacture of these implements from the late and quartz found on the beach near by. This Indian settlement was probably abandoned at the annihilation of the powerful Pequot tribe, to which they belonged, in 1637.

The Hammock was subsequently occupied by OBED and his tribe, from Niantick, on the western border of Rhode Island, and within the jurisdiction of the Connecticut colony at that time. The small tribe were living here at the time of the arrival of the first whites, and were known as the Menunketeset Indians. They returned to Niantick about the time of the King Philip war, in 1676."

http://www.dunhamwilcox.net/town_hist/westbrook_hist.htm

I can quote myself here:

"Histories of the Saybrook, CT area include mention of Obed and "Obed's Sacrifice Rock." Obed appears to have been a "son of a Hammonassett Chief; and after the subjugation of the Pequot, a servant to Gov. Fenwick: that Fenwick did give him...two acres more or less near the confluences of Pychaug & Menunketezuck rivers, known as Obed's Homake."

He later lived near Springbrook Rd, "passing most of his time in the retirement of his wigwam or the solitude of the chase." Obed's Sacrifice Rock was a boulder "contiguous" to his "aboriginal structure." The author continues to write in a language somewhat similar to American English, "Upon this symbol of pristine faith, was kindled from time to time, a fire which consumed the sacrifices tendered, with sweet incense from bay and birch; mingled with the fumes of tobacco." "

http://www.neara.org/macsween/macsween.htm

TOWN OF OLD SAYBROOK.

After the Indians were subdued, some of them were servants to the whites, and others lived near them and became partially civilized, many of them taking English names. They gradually decreased, however, till at the beginning of the present century, only a few stragglers remained. The tradition has come down to us, that Obed, one of these Indians, sacrificed a deer to the Great Spirit on a hill about half a mile north of the head of Main street. The hill is still known as "Obed's Alter Hill," though the exact rock on which the sacrifice took place is not known. It was, however, one of the high rocks on the east side of the hill, and it is not visible from the turnpike. Who this Obed was is not known, but an Indian of that name was a servant of Colonel FENWICK, and it is probable that he was the one. Years afterward he laid claim to a piece of land, which the following entry in the town acts explains: "The Teste of William HIDE and Morgan BOWERS, who certife & say that wee do well Remember that Obed the Indian was a servunt of Mr. FENWICK the space of four years, & we are able to say he was a faithful servant to him, & that for his service, Mr. FENWICK Did Ingage a parcel of Land to him, We cannot Justly Say what Quantity, But we Do conclude it was not less than four acres, and that Obed's father Did Possess the Land before the Serviss of the said Obed was out. To this we Can Safely take our oaths.

There's been lots of newer stone walls built since the 1600's, but I think I see the "Indian Look" of the oldest of stone rows (built very similar to rows I've follwed in Rhode Island) and I wish I'd had the time to just follow those stone rows rather than just glimpse them from my bicycle as I rode by, especially in the property newly acquired by the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge (http://www.fws.gov/refuges/profiles/index.cfm?id=53546).

But here's the one at the edge of the property.

In the distance is I-95; that sort of hump in the middle of this section of stone row is a sort section of stone row that ends with a big end stone above what's now a little pond, but probably was a spring:

I stepped onto the highway side to take this photo of it, a steep bank below the big stone at the right, a curious collections of smaller stones on the row to the right of the the big boulder in the middle...

The few stones I did pick up, I turned in my ands until I found some comfortable way to hold it...

.. hand axe, maybe...

.. hand axe, maybe...

...but I think it's that pile of stone tools, sitting on a stone row at a spring, maybe an old camp, maybe just a spot where tools were left rather than carry around hand axes and hammer stones, abraders and nut crackers and who knows what else, right there in my mom's backyard.

Monday, March 10, 2008

It's Time to "Wake Up"

“Native people’s histories and stories have been told by others – rather dispassionately at times and not always with accuracy. Something is missing when we cannot and do not know our true past. Something is terribly wrong when our past is not accurately recounted,” Trudie Lamb Richmond writes in Enduring Traditions; the Native Peoples of New England, edited by Laurie Weinstein.

And also to repost this from my very first post, explaining why this blog is called “Waking Up on Turtle Island:”

“It's been many years since I woke up to the fact that I live in a special place on Turtle Island.Not that I was actually asleep for a long period of time, but rather I gradually became aware that remnants of ancient stonework was all around me, dismissed as Colonial construction, but really (were actually) part(s of or, more accurately “remnants of,” that remain still to today) of a managed cultural landscape that may be hundreds or thousands of years old.”

To go back to sometime in the 1990s when I first met Trudie, I should add that she mentioned a book she had heard of called “Manitou,” that also suggested that there existed remnants of, as the full title of the book says, “The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization.”

To go back to sometime in the 1990s when I first met Trudie, I should add that she mentioned a book she had heard of called “Manitou,” that also suggested that there existed remnants of, as the full title of the book says, “The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization.”I ordered the book since I couldn’t find it in any libraries nearby and got it just in time to take with me on a family camping trip to Burlingame State Park in Rhode Island. It was a life changing experience to read that book in that place – and then to walk trails in the greater Charlestown area, following stone rows of all sorts. In particular I remember following one, inside the park itself, that was a spiral – a motif I’d seen before as petroglyphs and designs on Indian baskets.

The very first page I read in James Mavor and Byron Dix’s “Manitou” also led me to seek out a group they sent acknowledgements to, The New England Antiquities Research Association, or NEARA (http://www.neara.org/ ), which is how I first met Peter Waksman (http://rockpiles.blogspot.com/), who in turn introduced me to Norman Muller at a NEARA conference in Danbury CT.

I was very lucky to say the least to make all these associations.

I was also very relieved to find that other people were seeing the same things as I.

The sad part is that 17 years later for me (and much, much longer for others), the scientific community, for the most part, remains hostile to the idea that there still remains, on “Turtle Island,” an incredible amount of stonework that represents perhaps thousands and thousands of years of remnants of a Sacred Cultural Landscape, some of it hidden but also in plain sight along the scars of the present Cultural Landscape of the last five hundred years.

And I’ll add, “While more and more of it, through ignorance and prejudice, disappears every day.”

While there are some enlightened and courageous individuals doing ground breaking work to combat the bigotry of the scientific community, like Doctors Curtiss Hoffman and Lucianne Lavin for example, I think that the time has come for that community to “Wake Up On Turtle Island,” so to speak.

After all, the empirical evidence is literally “written in stone.”

Monday, January 28, 2008

First Zigzag

The swamp that became Lost Lake must've been dammed when I was a baby, maybe - this recent map above shows it as a body of water.

The swamp that became Lost Lake must've been dammed when I was a baby, maybe - this recent map above shows it as a body of water. This is not the actual row below, but there are many up there that look just like this pattern.

This is not the actual row below, but there are many up there that look just like this pattern. Eric Sloane in Our Disappearing Landscape offered this explaination, echoed by many other writers:

Eric Sloane in Our Disappearing Landscape offered this explaination, echoed by many other writers:

In another place, at a right angle and to the west of a very long zigzag row, an immense linear wall meets up with another zigzag row, blocked sort of by the big fallen tree:

In another place, at a right angle and to the west of a very long zigzag row, an immense linear wall meets up with another zigzag row, blocked sort of by the big fallen tree:

I would have stitched these three together, but somehow that panorama function has dissappered from the program it used to be in...