Multiple Layers of Meaning in the Mi'kmaw Serpent Dance –

Trudy Sable

“How far back this

dance goes among the Mi'kmaq is difficult to say. Possibly it originated from

the Ohio Valley where the serpent mounds of the Adena tradition are found:

interchange between the Ohio Valley and the Maritimes 3,000 years ago is

documented (Ruth Whitehead, personal communication, 1996).”

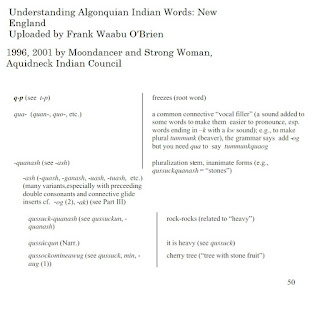

“First, as seen in the language, the world is experienced

and expressed as fluid, in a constant flux, or as a process, not static and

objectified. For instance, there are a number of words for Creator, e.g. kisu

Ikw, ankwey-ulkwjikeyulkw, tekweyulk, most of which are transitive verbs

describing different processes of creation that do not begin or end, but are

ongoing. The word adapted by the missionaries to communicate the abstract

concept of 'God' is Niskamij, which is both a kin term and an honorific term meaning

'grandfather', 'step-father', and 'father-in-law' (Francis, personal

communications, 1995-96).

Second, because of the fluid nature of reality, everything

in the culture seems to accommodate and adjust to a world of shifting

realities. Many of the legends are filled with shape-shifting and unpredictable

beings with whom one had to interact appropriately to survive. The nature of

the language, stories, songs and dances, all seem to be a way to re-create and

re-evaluate reality again and again, and to re-establish one's relationship

within it continuously. Third, everything expresses a world of relationships,

or things in association or in relation with other things, not existing as

separate entities. This can be seen in the language in the extension of kinship

terms to things, animals and other-than-human-beings, as well as in the social

organization. Similarly, the terms for colours illustrate this relational

quality. Except for the four colours red, black, white and yellow (also the

colours used for the four directions), all colours are associative — or

"analogized", as Francis (personal communications, 1995-96) terms it.

Even these four, however, are thought to have derived from Proto-Algonquian

words that associate them with blood (red), light/sunlight/dawn (yellow and

white), and ash (black) (Whitehead 1982:71). Other colour terms mean like the

sky' (blue), 'like the fir trees' (forest green), etc. Thus there is no way to

describe the colour of blue and green rocks, or even a dream of blue and green

rocks, without ascribing to them a connection, or relation, to the sky and fir

trees. Furthermore, all colours — including black, red, yellow and white — are

intransitive verbs that can be conjugated. The translation of maqtewe 'k

(black) is 'in the process of being black', inferring that there is no fixed

state of blackness, but rather a stage in a process that could change (Francis,

personal communication, 1996). Fourth, many levels of meaning can be compressed

into one word, one utterance, one step — a whole image that might take many

sentences in English to write out can be expressed in one word or one movement,

similar to mnemonic marks made to convey information, or wampum belts with each

bead associated with some message. As well, there may be implicit meanings that

are not conveyed in the literal translation of a word but simply come from

being part of the culture...

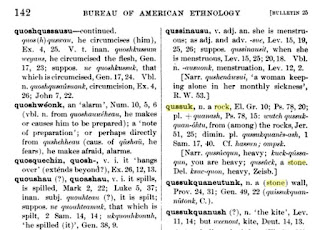

...The word jujijuajik, according to Margaret Johnson, means

'acting like a snake'. She explained that the word jujij refers to things that

crawl on the ground, e.g. snakes, lizards and spiders. This is in keeping with

Hagar who quotes Silas T. Rand, the 19th-century Baptist minister to the

Mi'kmaq, as defining jujij as a general term for 'reptile'. Hagar also mentions

that, despite this definition, several Mi'kmaq assured him it designated the

rattlesnake (Hagar 1895:37). John Hewson defined jujij as 'serpent' and

jujijuajik as 'they do the serpent', but Francis was uncertain that this was an

accurate definition. Nicholas Smith cites Jack Solaman, a Maliseet from Tobique

Point, as using the word al-la-de-gee-eh in a singing of the "Snake Song"

in 1915. This word was translated by Peter Paul as 'moves like a snake', though

it does not actually contain the word 'snake' in it; rather, it literally means

"it has the motion of a snake" (Smith n.d.).

In the Mi'kmaw language,

this would be alatejiey, which is translated as 'crawling around, or the

movement that the snake makes' (Francis, personal communication, 1996). This

translation seems similar to Margaret Johnson's definition of jujijuajik. The

actual word for 'snake' in Mi'kmaq is mteskm (Hewson, personal communication,

1996)...

...The Jipijka 'm is a powerful symbol in Mi'kmaw legends.

It lives and travels beneath the earth or water, and its horns, one red and one

yellow, were used for personal power particularly by puoinaq, or what are

referred to as shamans today. It can also take on human form and live as a

human in the underwater world. The red and yellow horns of the jipijka 'm are

power objects, and stories about the use of jipijka 'm horns are known all the

way across northern North America and across the centuries, back to northern

Asia (Whitehead, personal communication, 1996)...

Hagar describes it as "a horned dragon,

sometimes no larger than a worm, sometimes larger than the largest serpent...

He inhabits lakes, and is still sometimes seen" (Hagar 1896:170)...

In summary, the Serpent Dance involves many layers of

meaning and embodies a richness of information and profundity. First, this one

dance brings together a web or system of relationships that occur

simultaneously — the changing of seasons, most probably linked to the

appearance or position of a constellation in the sky, connected in turn to the

time of the moulting of snakes, which were indicators for the ripening and

picking of medicine.

On another level, the Jipijka 'm was the essence or

protector of medicine, which was the spirit ally of the puoin, who was the most

powerful shaman. Ultimately, the dance protected the well-being of the people

themselves. Second, the mirroring of one thing in another is evident — the

microcosm reflecting the macrocosm. The dance itself mirrored the sound of the

plant, the coiling and uncoiling of both the literal snake awakening from

hibernation and shedding its skin, and the essence of the medicine in the form

of the Jipijka'm, and possibly the constellation in the sky and the changing or

"turning over" of seasons. The plant, meteteskewey, may have mirrored

the Jipijka 'm in its appearance and sound, if the identification of the plant

is correct.

Possibly, as well, the constellation in the sky mirrored the cycle

of the snake on earth, like the constellation Ursa Major mirroring the

hibernation, birth, and hunt of the bear as it moves through the sky in the

winter and spring (see Hoffman 1954:253). Furthermore the male and female

dancers were possibly a reflection of male and fevna\e jipijka 'maq, as well as

the male and female plants. Finally, the dance illustrates the Mi'kmaw

relationship to the world as being part of universal processes and cycles, of

"tuning in" to the fundamental energy and rhythms and reflecting and

expressing those processes and rhythms in the dance. The dance was a means to

help effect the changing or turning over of seasons, and channel the energy

appropriately so that the medicine would be powerful and effective, just as

other aspects of nature — temperature, soil composition, weather patterns, etc.

-contribute to the process. Dance was a way to reflect and come to know the

world, embody and communicate its rhythms and its stories, and re-establish

one's relationship to and within a shifting reality again and again.”