From the Plantation’s

Watch House, the field full of “corn mounds,” where the Three Sisters of Corn,

Squash, and Beans grew together, could be easily seen. The same was true of the Nonnewaug Fish Weir, a stone wall-like diagonal row of boulders in the river, that gave the

name to The Nonnewaug Wigwams. Behind the Watch House, to the west, was the

Mast Forest, enclosed by a border of fireproof stones, a qusuqaniyutôk or

perhaps more accurately qusuqaniyutôkansh,

a series of segments of stone enclosures and entrances.

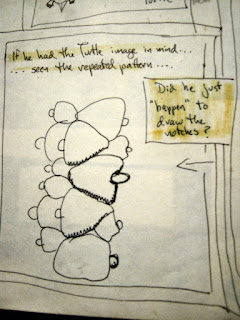

A definition or two, the former from the scientific literature emerging in the early 21st century, the latter mine, an artistic based impression based mostly on observations of "stone walls" over around thirty years at the time I’m writing this:

Qusukqaniyutôk : (‘stone row, enclosure’ Harris and

Robinson, 2015:140, ‘fence that crosses back’ viz. qussuk, ‘stone,’ Nipmuc or

quski, quskaca, ‘returning, crosses over,’ qaqi, ‘runs,’ pumiyotôk, ‘fence,

wall,’ Mohegan, Mohegan Nation 2004:145, 95, 129) wall (outdoor), fence, NI –

pumiyotôk plural pumiyotôkansh.)

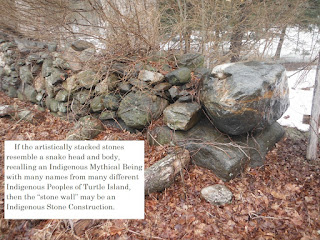

Qusukqaniyutôk: “A row of stones artistically stacked using elements of Indigenous Iconography, sometimes resembling a Great Snake, often composed of smaller snake effigies as well as other effigies both zoomorphic and anthropomorphic, sometimes appearing to shapeshift into another effigy, possibly related to control of water or fire (sometimes both) on Sacred Cultural Landscapes that are becoming to be recognized as Indigenous Ceremonial Stone Landscapes.”

Sometimes the enclosure has an abundance of blueberries in

it. Sometimes there’s a name (or a remembrance of an original name) such as

cranberry Pond or Cranberry swamp, inside a stone enclosure, surrounded by

other enclosures, fed by streams bordered by and sometimes diverted by rows of

stones emanating from stone worked springs.

Wildfires taught lessons to the People who first lived on the landscape and those Peoples learned to use fire to tend the landscape. It is my thought that those rows of stones, controlling fires and the flow of water, were built by the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern gate of Turtle Island, creating one of the “World’s Largest Rock Gardens.”

From little bits and pieces, remnants of old stones, remain while others are just thoughtlessly disturbed forever, lost pieces of a Sacred Indigenous Ceremonial Stone Landscape...

.jpg)