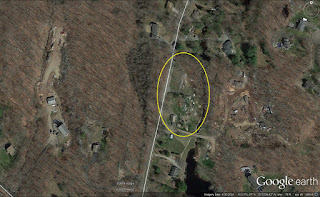

These are photos taken October 20-21, 2014 at the Norbeck

Section 2 prescribed fire being managed on State, Federal and private lands

approximately 4 miles northeast of Pringle, South Dakota.

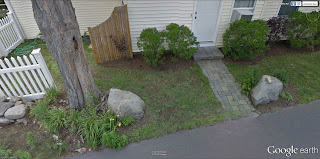

Imagine instead of wire fence and a mowed path,

a “stone fence" in New England.”

Imagine instead of a stone fence,

a long snake-like geoglyph or a Petroform Great Serpent at the Eastern Gate of

Turtle Island...

The Guarding

Great Stone Serpents, who know your intentions, who have been offered tobacco,

that enclose a place have been repaired. The firewood has taken away to the

enclosure where the wigwams are, and now the Ceremony continues as fires are being

set along those Guarding Serpents, burning toward the center...

Imagine a quarter

or perhaps half a million miles of rows of stones, stacked like snakes,

connecting yet separating Places on a Sacred Stone Landscape, , snake heads up

on the High Places, tails in the watery entrances to the Places where the Great

Serpents live and travel along.

And the whole

Stone Garden is dotted with stone mound monuments of many kinds, somewhat

similar yet each as individual as a snowflake...

Remember: these fires

are beneficial low ground fires, not destructive crown fires that consume all.

Note the trees

still standing above the blackened ground...

The Tribal Perspective of Old Growth in Frequent-fire

Forests—Its History

Victoria

Yazzie 1,2

“Native Americans used fire for hundreds to

thousands of years to manage forests and construct old-growth structure

before European settlement (Cronon 1983, Delcourt and Delcourt 1997, Anderson

2005). Details of these practices can be generalized from historic records and

reconstructions of habitat characteristics before European contact. Although

the intent to uncover history validates historic habitat structure, the

evidence of Native American influence is minimized or lost through

misinterpretation by non-Indian perceptions of American Indian history (Wilson

1996) and the effects of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) use (Simpson

2004). Native American people have long had an immediate relationship with

their physical environment and were cognizant of its rhythms and resources.

Their management of natural resources and the altering of landscapes with fire

are grounded in generations of accumulated wisdom and a reciprocal obligation

with all animals and inanimate beings (TEK; Simpson 2004)...

Colonization in New England began at a time

when the ecological conditions of extensive regions of North America depended

on prescribed fire use by Native Americans. The ecology of these landscapes

began to be changed by European settlers who altered the uses of the land, and

by the forced decline of the Native American people and their use of ecological

knowledge (Cronon 1983, Stewart 2002). Changing patterns of native resources

use by European invasion altered the physical and cultural landscape in this “New

World.”

To the Europeans,

the overall resource abundance of the New World—as evidenced by the old-growth

forests, large herds of animals, large flocks of birds—seemed infinite. The fur

trade and lumber industries opened the door to resource exploitation...

One can postulate that a similarity exists

between the reduction of old-growth forests and the decline of Native American

populations, which have been forced to assimilate, and the outlawing of their

TEK practices, such as the use of fire... Indeed, tribal communities have been preserved for centuries because of

their knowledge of the natural, spiritual, and ecological world, and their

understanding and respect for the interconnectedness between humans and all

other living things (Moller et al. 2004).

Combining Science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge:

Monitoring Populations for Co-Management

Henrik Moller1, Fikret Berkes2, Philip O'Brian Lyver1, and

Mina Kislalioglu2