Changing plans, I turn down White Deer Rock Road.

It’s the “back side” of Lake Quassapaug, the Middlebury end

Not the Amusement Park side but the Tyler Cove side.

New stone walls by the country club entrance,

Formerly a road that my grandmother and her brothers would

walk,

From the family farm, down to the Lake, to go fishing…

There’s no boat launch any more, no places to park on the

Cove

But there are still some trails visible, leading up to where

the Indian Fish Camp used to be.

Native people would camp there in the summer, they say,

From Waterbury and from Rhode Island and from all over, they

say.

I assumed they meant “Long ago,” but I once talked with a

Mr. Freeman

Who told me it wasn’t that long ago that he’d camp with his

Grandmother

And other “Woodbury Indians.”

-

“But I

just read a book that said there aren’t any more (Pootatuck) Woodbury Indians,”

I say.

-

“Well my

grandmother never must’ve read that book,” Mr. Freeman says.

Big new houses on the road but

there’s Nature Center signs here and there along new pavement

And I stop at the designated parking

spot a moment, look at the map and the broken rocky ground.

I realize that these outcrops

were quarried, with probably blasting caps and dynamite;

I can see the old truck paths, softened

with a hundred years’ worth of time,

Most likely back when Mr. Freeman’s father

and his crew,

Just my Dad’s grandfather and his

crew of a brother and a cousin,

Worked building the famous Whittemore

estate walls in the WPA years…

-

Mr. Freeman

tells me the story of the herd of White Deer that gave the road it’s name.

-

Almost

word for word, it’s the same story my grandmother told me…

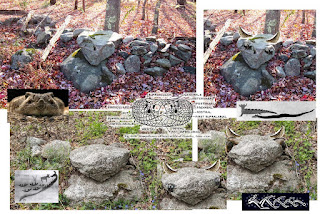

I spot a perched and pedestaled rhomboidal stone I had

photographed years ago,

A Healing Diamond perhaps, a Medicine Stone,

And although I’ll never know just who did that

I start to understand the intention of the person who placed

that Stone just so,

On the shattered remains of a Sacred Landscape…

http://wakinguponturtleisland.blogspot.com/2013/12/rhombus-stone-on-white-deer-rocks-road.html

https://wakinguponturtleisland.blogspot.com/2016/03/around-and-behind-rhomboidal-stone.html

%20snakefence.jpg)