Pages

Saturday, December 28, 2024

Saturday, December 07, 2024

"Oldest Stone Wall of 1607" (Maine)

“I found Rootes and Garden hearbs and some old Walles there, ...which shewed it to be the place where they had been...” Traveler Samuel Maverick, 1624, (said) of his visit to the site of the failed Popham Colony.

Not Stone fortifications, not stone fences, in the language of the times, but perhaps "walles" of timber framed houses?

New England Folklore claims the first “stone wall” was built in "Northern Virginia" by English settler colonists:

“The oldest known stone wall in America dates to 1607, built by English

settlers of the Virginia Company along the estuary of the Kennebec River north

of Portland, Maine.”

“On August 19 the colonists selected the site for Fort St George and read out the charter and laws. The site was chosen to be at the mouth of a great river giving them good access to the interior but hidden from direct view of passing ships. In the following weeks, they worked on building the fort, including digging trenches and other defenses such as gabions (cylindrical baskets filled with dirt or stone). One early priority was to build a storehouse so that they could offload their supplies and trade goods from the ships…”

https://mfship.org/history/popham-colony/

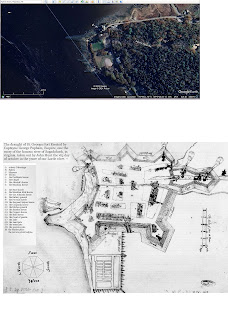

The model (below) shows no gabions (above),

and I think someone is showing the imagined "fortress walls" in the "draught" of the Fort,

the conjectured "first stone wall" often cited by a great number of authors.

“This model recreation, a gravel parking lot, and a large collection of artifacts are all that remain of an English colony established in 1607 in Phippsburg, Maine. The Popham Colony was the first organized attempt by the English to establish a colony on the shores of what we now know as New England. It was planted at the mouth of the Kennebec River in the summer of 1607 and lasted for little over a year until it was abandoned in the fall of 1608. To return home to England, the colonists constructed the first ship ever built in North America…"

Documents record that at Fort St. George the colonists built

a trenched fortification, a large storehouse, a chapel building, and a house

for Raleigh Gilbert. Shipwrights who accompanied the voyage constructed a small

vessel called a pinnace, which the colonists named the “Virginia” and sailed to

England on their return.

Scholars viewed the John Hunt Map with skepticism. President

George Popham sent to James I a report that the Native Americans say “there are

nutmegs, mace and cinnamon in these parts” and that just seven days away lies

“none other than the Southern Ocean, stretching towards the land of China:” the

fabled and sought-after northwest passage.

The Hunt Map, in the permanence of the fortifications it

shows, number of structures, elaborate gates, and especially its almost

whimsical embellishment, similarly strains credulity. John Hunt enlivened the

map with fiery blasts from the cannon, pennants flapping atop rather fantastic

crenelated gates, and a walled garden outside the ramparts. “A lot of us poo-poohed

the map,” says Pemaquid, Maine archaeologist Neill DePaoli, as “highly

exaggerated fiction, created trying to promote things back home.”

Still, the map had been taken seriously enough to inspire

1962 and 1964 Sabino Head excavations by Wendell S. Hadlock. He trenched

extensively, but found no foundations of stone. He did dig through evidence of

burning, and uncovered a few artifacts, notably North Devonshire sherds, but at

the time he could not date these with precision. Hadlock concluded that at best,

while the site might be Popham Colony, erosion and disturbances left little

remaining. Reviewing Hadlock’s notes, Brain felt the same results did not rule

out the presence of the colony. Hadlock could easily have missed Fort St.

George, expecting obvious foundations and using relatively crude methods.

Hadlock dug only the width and depth of a shovel blade, and failed to note such

basics as vertical position of the artifacts discovered.

Brain agreed that the map exaggerated. The colonists had 52

days to build before October 8, 1607, the date of the map; John Hunt must have

drawn structures from his imagination. But Brain’s walk told him the modified

star shape fit the land well. And hadn’t the colonists accomplished much? They

built a fortification with buildings (numbered by one source in Thayer [1892]

at “50 howses therein”), explored the Maine coast and interior, and built the

“Virginia.” To Brain, at the worst, the question posed was: How much of it is

real, how much, fancy?

https://www.athenapub.com/AR/10popham.htm

12/0/2024 - I had posted this link in error (interesting as it is): https://nature.berkeley.edu/departments/espm/env-hist/articles/73.pdf

"Though the Hunt map indicates the fort covered a footprint

of just one-half of a hectare (one and one-quarter acres) and an interior area

of one-third of a hectare (one- eighth acre), the impression it evokes is of an

extensive walled village with all of the necessary accouterments. According to

its date, the map illustrates the situation as of October 8th 1607, less than

two months after the colony's founding. The short time between the founding of

the colony and the drafting of the map has left many researchers incredulous.

It is commonly speculated that the map was partially a plan of what the

colonists intended to be build, rather than a record of what was already built.

It has been pointed out that the leaders would have desired to give their

backers in England the most optimistic reports possible, and that the Hunt map

would have played into that effort. The map also can be viewed as a stylized

illustration. 11-13

Prior to its settlement by the Popham Colonists, Hossketch

Point was occupied from time to time by local Wabanaki. After the colony was

abandoned, the Wabanaki made brief stays on the point once again. Apparently,

Europeans and their cultural descendants did not reoccupy the point until early

in the 1800s when a Mr Hill established his homestead.~' Through the nineteenth

century, several additional houses and farmsteads were built and maintained on

the point.

As of the end of excavations in 2002, evidence of the fortification trench and five buildings

that stood inside of the fort have been uncovered…Undoubtedly, a considerable

part of the construction was carried out by relatively unskilled laborers.

Indeed, some of the simpler forms of earthfast structures, such as those raised

on forked poles called cratchets, might have been built entirely by unskilled

laborers

20-21

In England, timber framing was a construction method most

commonly associated with the eastern and southeastern counties. Builders in

Western England were more likely to use cruck framing, when they built with frames

at all, or to build mass walls of stone or cob (mud).25

Fort St. George was not simply an English village, and the

culture reproduced there was not simply English domestic culture. Rather, Fort

St. George was one in a series of related English colonizing efforts. The

connections between these efforts suggest a simple mechanism by which the

experiences of each failed colony fed into a common pool of developing ideas

about how colonies should be organized, equipped, and manned. The growing body

of knowledge could easily have encompassed ideas about what kind of English

buildings would be most suitable in establishing new settlements.

Fort St. George was built and abandoned in less than 14

months. Faced with novel conditions, such as an abundance of timber, and new

kinds wood, the colonists may well have made innovations in the way they

approached the building. Essentially, however, the entire store of knowledge

that the colonists possessed came with them on Mary and John and Gift of God.

As Abbott Lowell Cummings wrote in his classic book The Framed Houses of

Massachwetts Bay, 1625-1 725:

The immediate background of this dominant [English] majority

among the earliest inhabitants is thus a matter of basic concern. The observer

must be able to recognize the evolutionary changes that occurred in

postmedieval vernacular buildings during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth and the

early Stuarts. He must know the exact level of development and the character of

these humbler English houses at the opening of the seventeenth century in terms

of plan, construction technology, and regional stylistic differences if he is

to understand fully the structures built by Englishmen in the New World

throughout the &st century of settlement. p26

Where many posts are to be set close to each other, as in a

palisade, a trench may be used in place of individual holes. Trenches are

conceptually similar to holes, and their fill will exhibit the same kind of

mixing as in postholes. Such trenches are a subset of a larger group of

features known to archaeologists generically as "builder's trenches"

or "construction trenches."

Conclusions Initial reports to England were promising: work

on the fort moved apace, relations with the native Wabnaki were cordial, and

according to the Wabnaki, all of the treasures that the English sought were to

be found within easy tra~el.~' By the end of the fist winter, however, the

outlook became more bleak. According to Ferdinando Gorges, the storehouse

burned along with much of its contents.92 Of the promised riches, only timber,

fish, and k s appeared forthcoming, and at this early date, these were not

enough to maintain the enthusiasm of the colonists. George Popham died and

Raleigh Gilbert replaced him as president. Reportedly, this led to a souring of

relations between the colonists and the neighboring News from England that both

John Popham, the colony's chief political backer and financier, and John

Gilbert, Raleigh Gilbert's elder brother, had died completed the dl fortune.

The colonists sailed away to England before a second winter could take hold,

and Gorges' remark above provides a concise epitaph.

But the colonists left their mark on the ground, albeit less

of one than they hoped.

When a shipload of Frenchmen visited the Sagadahoc in

October 1611, they easily found the abandoned fort. Impressed, they began

"praising and boasting" of the English enterprise, though, alas, they

did not itemize what they found..." page 94

voyages: https://archive.org/details/earlyenglishfren02burr/page/n9/mode/2up

Saturday, November 02, 2024

What Kind of Farmers (Made that "Stone Wall")?

Farmers of Corn, Squash, and Beans?

Farmers of Cranberries, Blueberries, and

Mast Forests??

“Just some

rocks, of course” someone else says,

And of

course I’m thinking “You mean stones.”

“Farmers

clearing their fields, of course,” someone agrees,

“Happened

all over New England, lol!” someone else

proclaims,

And of

course I’m thinking “What kind of farmers?”

And of

course I know who he means:

-

Dutch Farmers

-

English Farmers

And, of

course, all those Farmers who came after them,

Bringing

pigs and cows and sheep

Wheat and

peas and “Old World Crops”

To the mythical

howling and empty wilderness of these “New World Lands.”

And of

course I’m thinking they think:

“Nothing

happened here before 1620.”

And of

course he doesn’t have a clue what I mean:

The Farmers

planting “Corn, Squash, and Beans,”

By the Stone Fish Weirs in the floodplains

-

Lenape Farmers of Forests and Grasslands

-

Paugussett Farmers of Blueberries and

Cranberries

And of

course all those who came before them

On these Ancient

Homelands,

Over

thousands and thousands of years

I’ll say it

again:

Over

thousands and thousands of years…

“We didn’t

build walls,” someone else says

And I know

she means the “stone fences” almost everybody colloquially calls “stone walls,”

Here on the

Eastern Gate of Turtle Island that almost everybody calls “New England,”

Almost

always assumed to be post contact constructions related to

European

ideas of property ownership,

European animal husbandry,

And European

agriculture,

Here where

all the “Real Indians” are said to be extinct,

Here where

the Puritan Saints declared:

Indians had

no art and “enclose no land,”

Here where

nomadic Indians wandered like houseless people,

“Like the

foxes and wild beasts,”

Here where

the Indians, they said, worshipped the bright red devil…

But I’m

talking about the Qusukqaniyutôkansh, the Rows of Culturally Stacked Stones,

That snake

along the ancient roadways, that enclose the ancient gardens,

That follow

the path that water takes from hillside springs to the salt water,

That continue

to get eaten up, bulldozed and buried, or maybe washed away,

That

continue to be dismissed as “linear garbage piles” by Colonialists, Denialists,

and Nationalists,

All of whom

claim to be experts and scientists, supposedly exposing the pseudoscience,

Exposing the

academic fraud of a perceived Ceremonial Stone Landscape Movement,

Often in the

form of an angry condescending ad hominem tirade

Rather than

an actual investigation of the Rows of Culturally Stacked Stones,

The “stone

fences” almost everybody colloquially calls “stone walls,”

Here on the

Eastern Gate of Turtle Island that almost everybody calls “New England,”

That

sometimes begin with what appears to be Snake head…

Of course I find I agree with that statement...

"Qusukqaniyutôk: (‘stone row, enclosure’ Harris and Robinson, 2015:140,

‘fence that crosses back’ viz. qussuk, ‘stone,’ Nipmuc or quski, quskaca,

‘returning, crosses over,’ qaqi, ‘runs,’ pumiyotôk, ‘fence, wall,’ Mohegan,

Mohegan Nation 2004:145, 95, 129) wall (outdoor), fence, NI – pumiyotôk plural

pumiyotôkansh.)" - Nohham Rolf Cachat-Schilling

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 77, No. 2 Fall

2016

https://vc.bridgew.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1202&context=bmas

Friday, October 18, 2024

More of the Final Days of the Nonnewaug Fish Weir

Nonnewaug

People around here say the name every day, but what does it mean? It's a descriptive place name, used by the Indigenous Peoples who lived here in Pootatuck for thousands of years before 1673, when a group of settlers from Stratford moved into the area, originally the "Pomperaug Plantation."

According to William Cothren, who wrote several volumes of the "History of Ancient Woodbury," it means "The Fresh Water Fishing Place." Cothren seems to quickly forget that thought after briefly stating so and then begins misinforming people that all these things named Nonnewaug are named after the Sachem or "Chief" Nonnewaug, much in the same way that the place name Waramaug, the "good fishing place," and the Sachem Waramaug were rather incorrectly turned into a personal name.

Cothren, William

1854 “History of Ancient Woodbury Volume I.” Waterbury CT

1872 “History of Ancient Woodbury Volume II.” Woodbury CT