Saturday, January 15, 2022

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Just for the Record

Above: Slide from Power Point Presentation by Timothy H.

Ives

“A Brief Social History of Stone Heaps” Apr 23, 2021 https://youtu.be/rQV05I4N6O8

Just for the record: My first name is Tim, not Timothy.

Just for the record: I was a NEARA member for one year

although I wrote up some guest pieces for the online magazine.

https://wakinguponturtleisland.blogspot.com/2007/01/indian-cave.html

Just for the record: That “Indian Cave” may be an example of a stone sweat lodge rather than a hypothesized sheep barn since “Indians did not build with stone until taught to do so by European settler colonists” - in this part of the world, anyway.

https://wakinguponturtleisland.blogspot.com/2011/12/indian-cave.html

Just for the record: One of those stone features in Pennsylvania mentioned in “Stone Rows and Boulders; a Comparative Study” by Norman Muller

{ https://rock-piles.com/stonerows.pdf } dead link in 2022

(Muller, Norman E. “Stone Rows and Boulders: A Comparative Study,” New England Antiquities Research. 7. Association, 1999 Traditional Cultural Places - October 27, 2022

https://parkplanning.nps.gov › showFile )

has a “preliminary” date of 500 BCE attached to it:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0197693120920492

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

What IS Wrong with Our "Stone Walls?"

“Most of us today have had no experiences to challenge that view.”

Here’s another article I somehow missed

until just this morning, from somewhere in Massachusetts, where I think I may

have seen one or two photos of suspected Indigenous Stonework, if I recall

correctly:

“What's Wrong with Our Stone Walls?” - Acton

Historical Society – (11/16/2019)

https://www.actonhistoricalsociety.org/blog/whats-wrong-with-our-stone-walls

Of course this article tells that “One of

New England’s familiar sights is a stone wall in a forest, a remnant of land

use in days gone by.”

Of course this article tells us: “Based on

what we can see, many of us assume that farmers would have removed the many

rocks from their fields and stacked them in two- to three-foot-high walls to

delineate their property from their neighbors’ or to serve as a barrier to

animals. The former landscape that we envision

would have been open fields and gardens surrounded, if not by wooden fencing,

by relatively low stone walls.”

Of course this article tells us: “Most of us

today have had no experiences to challenge that view.”

Of course I am going to disagree with that

statement, thirty plus years into experiences that have caused me to think very

critically about challenging the idea that “stone walls” arrived sometime after

1492 or 1620 or perhaps the time when Indigenous

Homelands turned into Plantations in the New England town you might perhaps

live in, have visited or plan to visit.

The

Acton Historical Society tells us: “Visitors to our recently refurbished

landscape are surprised to discover that above our stone walls at the Hosmer

House are crossed, wooden poles. Why

would we ruin the look of “iconic” stone walls?”

I’ll partially

credit the Historical Society for telling us: “As it turns out, while our

imagined Massachusetts farm landscape is not entirely fictitious, farmers often

supplemented their rock walls with wood to make enclosures higher and less

likely to let animals escape.”

Of course I am going to disagree when they

repeat this same old story: “According to Robert Thorson’s Stone by Stone, a

hybrid fence of stone on the bottom and wood on the top was very common. The stone walls, in many cases, were “linear

landfills” to give farmers somewhere to put the rocks cluttering their fields,

and the wood raised the height of the fences to the 3.5-5 feet considered

necessary to block the movement of animals.”

In my experience, in my neighborhood, where an English Plantation collided with a Late Woodland/Contact-era Indigenous Village known as the Nonnewaug Wigwams in 1672 (or 1673), the oldest of the “stone walls” may have already been there, separating yet connecting sections of land. One could say that here in Nonnewaug (and beyond), “Stone walls parse the land into finer pieces, creating diverse microclimates and ecosystems and opportunities for creatures of all types,” as Robert M. Thorson is quoted as saying in “Stone Walls are a Habitat All Their Own” by Joe Rankin (Mar 16, 2018), found here:

The Acton Historical Society closes their

article by telling us that “(The) new walls are a reminder that we need to keep

our minds open to learn more about the lives of Acton’s former residents. Even commonly-held ideas of how things were

in earlier days may simply reflect the fact that our frame of reference is very

different from theirs.”

Of course I am going to tell you that yes we

do need to keep our minds open about the lives of the former residents of what

has been called New England (and beyond)for just a few hundred years.

Of course I am going to invite you to

consider that some “stone walls” and other “stone structures” are beginning to

reveal construction dates that go back hundred and even thousands of years, as

more sites are investigated, especially when optically stimulated luminescence

(OSL) is being used to test soil samples:

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query Acton: https://rockpiles.blogspot.com/search?q=Acton

Monday, January 10, 2022

Inventory of Stone Features (Hopkinton, Rhode Island)

From:

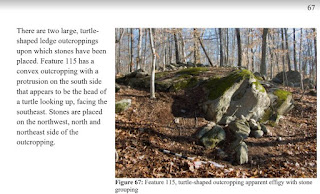

Historic Survey and Inventory of Stone Features Located Within the

Manitou Hassannash Preserve, Hopkinton, RI. Submitted to the Town of Hopkinton,

July 2020.

Martin, Alexandra; Eva Gibavic, Kenneth Leonard, and Richard Prescott.

https://www.clresearch.org/past-projects

“Stone rows, enclosures, structures and chambers can be found in the landscapes of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Structures similar to those shown in the cover photo are documented elsewhere. The age, cultural affiliation, and purpose of these stone structures--which are found in a variety of forms, such as piles arranged in spatial configurations across landscapes, shapes suggesting animal effigies, platforms and chambers--have been the subject of much debate. Some have argued they are remnants of colonial agricultural and storage practices; others that they are prehistoric Native American ceremonial structures. Ascertaining the time periods of their creation had previously been impossible. We felt that optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) had the potential to provide meaningful insights into their origins. In June 2018, samples for luminescence dating were taken from three sites: the Pratt Hill Site near Upton, located in south central Massachusetts; the Tolba Site of Leverett, located in western Massachusetts; and the Site of Hopkinton, Rhode Island. These samples were taken from hand-dug pits beneath stone structures to depths past modern soils into the geomorphic feature upon which the stones were placed (i.e. alluvial fan or terrace). The object of this excavation was to date the placement time of the stones onto the geomorphic feature...

...The age of the sample from the Site of Hopkinton, Rhode Island is in the range of 1570-1490 C.E (or 490 plus or minus 40 years ago).”

Sunday, January 09, 2022

Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) & Ceremonial Stone Landscape features

'"Some have argued they are remnants of colonial agricultural and storage practices; others that they are prehistoric Native American ceremonial structures...Clearly, further work is warranted at these and other sites, since the older age of 3,595 ± 260 years is an intriguing and valued look into the earliest dates of construction to these features." - Shannon Mahan

Optically

Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) data and ages for selected Native American Sacred

Ceremonial Stone Landscape features--Final Project Report Submitted to the

Narragansett Tribal Historic Preservation Trust

“Stone

rows, enclosures, structures and chambers can be found in the landscapes of

Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Structures similar to those shown in the cover

photo are documented elsewhere. The age, cultural affiliation, and purpose of

these stone structures--which are found in a variety of forms, such as piles

arranged in spatial configurations across landscapes, shapes suggesting animal

effigies, platforms and chambers--have been the subject of much debate. Some have

argued they are remnants of colonial agricultural and storage practices; others

that they are prehistoric Native American ceremonial structures.

Ascertaining

the time periods of their creation had previously been impossible. We felt that

optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) had the potential to provide meaningful

insights into their origins. In June 2018, samples for luminescence dating were

taken from three sites: the Pratt Hill Site near Upton, located in south

central Massachusetts; the Tolba Site of Leverett, located in western

Massachusetts; and the Site of Hopkinton, Rhode Island. These samples were

taken from hand-dug pits beneath stone structures to depths past modern soils

into the geomorphic feature upon which the stones were placed (i.e. alluvial

fan or terrace). The object of this excavation was to date the placement time

of the stones onto the geomorphic feature. Luminescence chronology is an ideal

scientific measurement, since the physics of the phenomenon mean that it dates

the last time mineral grains of quartz and feldspar were exposed to sunlight or

heat above 150 °C. All sediment samples were dated using OSL on very small

aliquots of <50-10 grains.

The age

of the sample from the Site of Hopkinton, Rhode Island is in the range of 1570-1490 C.E (or 490 ± 40 years ago).

The ages of the samples from Pratt Hill near Upton,

Massachusetts, at a site that was recently desecrated by being scraped off the

boulder foundation it was originally built on, are 1475-1375 C.E. (595 ± 50 years) for the top sample and 1315-1835 B.C.E (3,595 ± 260 years) for

the bottom sample. These samples were obtained from dust or loess that had

blown into the structure and collected in the scooped out hollow of the boulder

foundation.

The ages of the Tolba site in Leverett,

Massachusetts cover the ranges of 1670-1510 C.E. (430 ± 80 years), 1730-1570

C.E. (370 ± 80 years), 1420-1220 C.E. (700 ± 100 years) at the base. A sample

obtained beneath a housing foundation and into the land surface very near to

this site also gave an age range of 1470-1230 C.E. (670 ± 120 years). A brick

used in the house manufacturing was also taken back to the lab for luminescence

dating but data are not available at this time.

Construction ages of the Upton Stone Chamber: Preliminary findings and suggestions for future luminescence research

Shannon A. Mahan a, * , F.W. Martin b, c , Catherine Taylor c, d a U.S. Geological Survey, Denver Federal Ctr., MS 974, Denver, CO 80225-5046, USA b Massachusetts Archeological Society, 50 Village Ave., Dedham, MA 02026, USA c New England Antiquities Research Association, 58 Cortland Road, Milford, NH 03055, USA d Town of Upton Historical Commission, 14 Plain St, Upton, MA 01568, USA

https://www.uptonma.gov/sites/g/files/vyhlif5121/f/uploads/upton_stone_chamber_-_preliminary_findings.pdfIn a previous study of OSL dating performed on

sediment from the Upton Chamber Site, it was established that European contact

was documented in Plymouth at 1620 C.E., in Boston at 1630 C.E. and Upton at

1660 C.E. It is interesting that most of the currently sampled stone ceremonial

structure ages are falling in the Upton time frame (455 to 580 years ago, with

one lower age at 700 years) except for the lower Pratt Hill sample, which is

considerably older than any other previous age obtained.

One theory

is that the ceremonial structures were sacred sites that were cared for and

maintained during the years of sole Native American occupation. This theory

postulates that as Europeans settlers disseminated across the landscape, the

disease and displacement they brought largely ended the Native population’s

ability to maintain these sites and that the OSL dating documents this time of

disrepair instead of an original placement of stones on a geomorphic surface.

Clearly, further work is warranted at these and other sites, since the older

age of 3,595 ± 260 years is an

intriguing and valued look into the earliest dates of construction to these

features.

Shannon Mahan

smahan@usgs.gov

Data Source:

Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

From the Plantation’s Watch House

From the Plantation’s

Watch House, the field full of “corn mounds,” where the Three Sisters of Corn,

Squash, and Beans grew together, could be easily seen. The same was true of the Nonnewaug Fish Weir, a stone wall-like diagonal row of boulders in the river, that gave the

name to The Nonnewaug Wigwams. Behind the Watch House, to the west, was the

Mast Forest, enclosed by a border of fireproof stones, a qusuqaniyutôk or

perhaps more accurately qusuqaniyutôkansh,

a series of segments of stone enclosures and entrances.

A definition or two, the former from the scientific literature emerging in the early 21st century, the latter mine, an artistic based impression based mostly on observations of "stone walls" over around thirty years at the time I’m writing this:

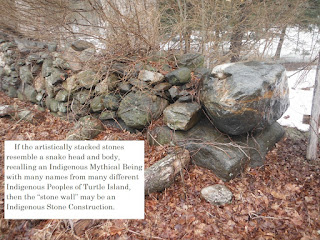

Qusukqaniyutôk : (‘stone row, enclosure’ Harris and

Robinson, 2015:140, ‘fence that crosses back’ viz. qussuk, ‘stone,’ Nipmuc or

quski, quskaca, ‘returning, crosses over,’ qaqi, ‘runs,’ pumiyotôk, ‘fence,

wall,’ Mohegan, Mohegan Nation 2004:145, 95, 129) wall (outdoor), fence, NI –

pumiyotôk plural pumiyotôkansh.)

Qusukqaniyutôk: “A row of stones artistically stacked using elements of Indigenous Iconography, sometimes resembling a Great Snake, often composed of smaller snake effigies as well as other effigies both zoomorphic and anthropomorphic, sometimes appearing to shapeshift into another effigy, possibly related to control of water or fire (sometimes both) on Sacred Cultural Landscapes that are becoming to be recognized as Indigenous Ceremonial Stone Landscapes.”

Sometimes the enclosure has an abundance of blueberries in

it. Sometimes there’s a name (or a remembrance of an original name) such as

cranberry Pond or Cranberry swamp, inside a stone enclosure, surrounded by

other enclosures, fed by streams bordered by and sometimes diverted by rows of

stones emanating from stone worked springs.

Wildfires taught lessons to the People who first lived on the landscape and those Peoples learned to use fire to tend the landscape. It is my thought that those rows of stones, controlling fires and the flow of water, were built by the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern gate of Turtle Island, creating one of the “World’s Largest Rock Gardens.”

From little bits and pieces, remnants of old stones, remain while others are just thoughtlessly disturbed forever, lost pieces of a Sacred Indigenous Ceremonial Stone Landscape...

Saturday, December 25, 2021

The 97% Solution

“Evaluations of qusuqaniyutôkansh (“stone walls”) by parties who do not test their hypotheses against Northeast Algonquian cosmology, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Rituals of Renewal on Ceremonial Stone Landscapes are doing, at best, only 3% of an investigation,” remarked Sherlock Stones to his associate, famed Rocket Surgeon John Possum. "The late Dr. Brian Jones, the Connecticut State Archaeologist spoke and wrote about that "Other 97% of the Human History," the Indigenous Peoples' History, that most people are almost entirely unaware of - or are greatly misinformed about."

“Call it “The 97% Solution,” Sherlock continued. “For thousands and thousands of years, the Indigenous Peoples of what is thought of as quaint “New England” certainly had a greater opportunity to shape the landscape, using fire and (hearth-like) fuel break rows of stones than the post contact Euro-American Settler Colonists and their slaves, indentured servants, employees, and their exceptional descendants with their “Merino Sheep Walls” and soil cutting plows in the remaining 3% of the human history of the region. The example of the use of LiDar in Central and South America to reveal and discover the vast amount of Indigenous Stonework in a place where “true civilization” was thought impossible to exist in a “pristine jungle” serves well. If those southern regions were transformed into some of the world’s largest gardens, then why would it be impossible that the Indigenous Peoples at the Eastern Gate of Turtle Island, the Dawnland, could create one of the “World’s Largest Rock Gardens,” my dear Possum?”

Dr.

Possum sighed and remarked, “Well Stones, what is the truly more advanced

civilization – one that creates a sustainable system of coexistence with the

ecosystem or one that degrades it to such a degree that, if continued without

change, in all probability leads to extinction?”

Both men paused, pondering this.

"Another slice

of Christmas Pie?" asked Dr. Possum.

"A plum of an idea," replied Sherlock Stones.

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Nonnewaug, the "Fresh water fishing place"

This diagonal line of boulders in the Nonnewaug River in Woodbury CT, most likely a diagonal fish weir that is probably the source of the place name Nonnewaug, just might soon disappear. Maybe on Monday, I don't know...

The years have not been kind to the Weir since that photo above was taken in 1997. That large tree crashed through the weir and started its demise...